This is a syndicated post that first appeared at http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/research/advancements-in-research/fundamentals/in-depth/when-east-meets-west

By Catherine Gara

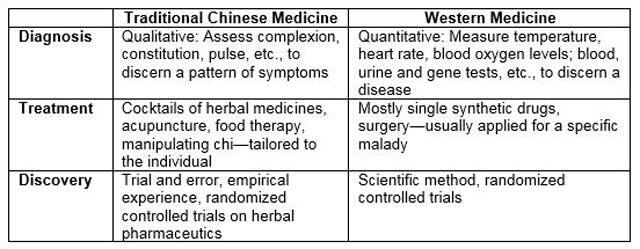

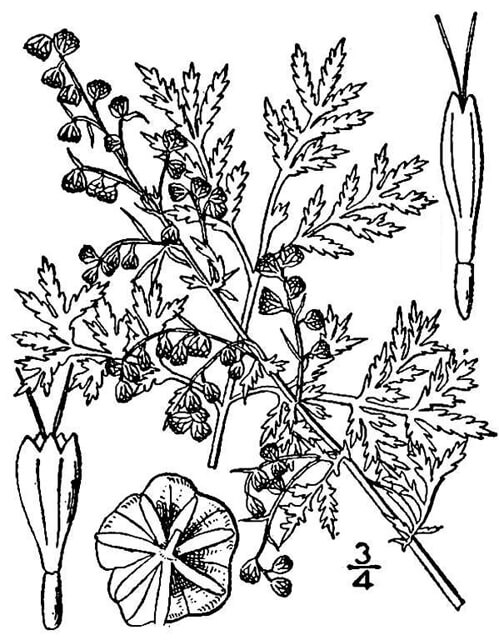

In 1969, Chinese researcher Youyou Tu was recruited to Chairman Mao’s top-secret Project 523 to help find a new drug to treat malaria. This October, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering the lifesaving drug artemisinin in extracts of Artemisia annua L., a plant known to Chinese to have medicinal properties since at least the fourth century. Her win has brought renewed attention to the dynamic relationship between Chinese and Western medicine. At Johns Hopkins, two faculty members from very different fields are exploring that relationship in their own ways: one by studying its history, the other by figuring out how one traditional Chinese medicine works.

From Plant to Pill

While Tu found inspiration in a document hundreds of years old, Jun Liu’s nudge toward Chinese medicine was more modern: a billboard. Liu, a professor of pharmacology and molecular sciences, was in China for a conference in 1993. “I walked out of my hotel, and there was this billboard advertising an extract from the thunder god vine as a novel immunosuppressant. I was already working on two immunosuppressive drugs isolated from microbes, so this piqued my interest. I went to the drugstore to buy a bottle of the extract and then read what I could find about it when I got back to my lab, then at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.”

The Chinese billboard that inspired Liu to study thunder god vine extract.

The Chinese billboard that inspired Liu to study thunder god vine extract.Liu caught a break: Another scientist had already purified the active ingredient in thunder god vine and chemically characterized it 20 years earlier. But its mode of action was still unknown, making the compound exactly the type he likes to work on.

“We work with natural compounds that have already been purified, characterized and identified as potent against cancer or some other condition,” he explains. “Then, we figure out how they exert their biological activity.”

He says that knowing a compound’s mechanism of action facilitates its development into a good drug because compounds are often toxic or unstable, or don’t get to the organ they need to. Before tweaking a compound to try to resolve those issues, it’s best to first know which protein a compound interacts with and how. “That way, you know where you can make chemical modifications without losing biological activity,” says Liu.

Tripterygium regelii, or thunder god vine

Tripterygium regelii, or thunder god vineCredit: Qwert1234 [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

For the compound extracted from thunder god vine, triptolide, that story is still ongoing. Most recently, Liu’s team published results showing that the compound halts cell growth by binding to the XPB protein, which is involved in manufacturing RNA and repairing damages to DNA. Derivatives of triptolide are already in use in the clinic, but Liu thinks there’s room for improvement. “Right now, we think of triptolide as the explosives you pack into a missile. It’s too toxic to be let loose,” he says. “So we’re engineering a ‘missile head’ for it, to direct it solely to cancer cells. We should know in a few years’ time if it works.” If it does, traditional Chinese medicine will have provided another successful lead for Western medicine.

More Than a Second Language

The history of Chinese medicine and its relationship with Western medicine are some of the topics of Marta Hanson’s work. Now an associate professor of the history of medicine, she first encountered Chinese medicine as a teenager in the late 1970s when she started studying Chinese in high school and took a course in acupuncture. Puzzled that her acupuncture teacher knew no Chinese, she set out to read Chinese medical texts in their original language. She now studies those original texts in their historical contexts to better understand their history on their own terms as well as interactions between Western and Chinese medicine. “To understand our present, we need to know where it came from,” she explains. “I study the history of Chinese medicine not to extract something clinically useful, but to learn how and why things change over time.”

Hanson says Western and Chinese medicine met in the early 1600s when Jesuit missionaries arrived in China and began translating Western distillation techniques and anatomy texts into Chinese. Over time, Western influence led to the formalization of Chinese medicine, arguably culminating in Chairman Mao’s creation of integrated academic and medical institutions, like the one where Tu did her Nobel work.

Artemisia annua

Artemisia annuaCredit: USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / Britton, N.L., and A. Brown. 1913. Illustrated flora of the northern states and Canada. Vol. 3: 526.

Hanson calls researchers like Liu and Tu “medically bilingual.” “The two systems of medicine are often mutually incommensurable, so you have to know a lot more than just an extra language to be able to blend them together in a meaningful way,” she says.

According to Liu, even the meaning of “traditional Chinese medicine” is hotly debated, but it generally involves three components: herbal concoctions, acupuncture and the concept of “chi,” or vital “energy-matter.” Some call it nonsense because they claim that it has no grounding in quantitative science and randomized clinical trials, despite decades of scientific research on various aspects of its therapies. Others, like Hanson, claim it has not only historical value but also value as a treasure house of empirical knowledge—with caveats. “Chinese medical therapies wouldn’t be in demand around the world if they did not meet the needs of patients who either culturally feel more comfortable with them or are dissatisfied with what Western medicine is able to provide,” she says.

She thinks of traditional Chinese medicine as a mirror that reflects back to modern biomedicine not its full image in reverse, but its shortcomings. And the reverse can be said about modern biomedicine as a mirror on traditional Chinese medicine’s limitations. Namely, what biomedicine is good at—evidence-based medicine, targeted treatments, modern pharmaceuticals—traditional Chinese medicine has to work on; and what traditional Chinese medicine is good at—considering the whole patient, individualized treatment, natural remedies—modern biomedicine could work on. “I think we can learn from that mirror to better understand both systems and hopefully improve them in the process,” she says.